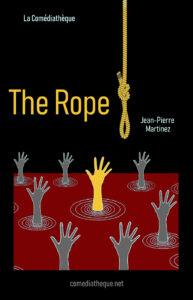

In a country under the grip of a tyrant, as dissent simmers and repression rages, a doctor and a priest clash over whether the sacred duty of their respective roles outweighs that of the citizens they both are. The stakes are nothing short of the life or death of the dictator and consequently the survival of the regime or hastening its downfall…

Original title in French : La Corde

English translation by Anne-Christine Gasc

Keywords : Participatory Theater, Political Theatre, Dramatic comedy

Cast : 2 characters (2 men)

A play written in March 2024

Political Analysis of The Rope

The Rope is a closed-door play set in the office of a military doctor within the Presidential Palace of a dictatorial regime. The presence of a grand portrait of a general signifies the ruling tyranny. The confrontation between the doctor and the priest, the central characters of the play, serves as a pretext for a political and moral reflection on power, individual responsibility, and the legitimacy of resistance against oppression.

1. An Oppressive Political Context

The play is rooted in a clearly dictatorial political framework, where:

- The repression of opponents is systematic: arbitrary arrests, bloody suppression of protests, and assassinations disguised as suicides.

- The state controls all aspects of society: medicine and religion are instrumentalized to uphold the tyrant’s power.

- Institutions are corrupt and powerless: justice is nonexistent, and intellectuals and elites are either complicit or forced into silence.

The plot revolves around a crucial dilemma: the doctor, who holds vital medical information, must decide whether to save the dictator’s life, knowing that his death could lead to the fall of the regime.

2. An Ideological Duel Between Science and Faith

The doctor and the priest embody two opposing worldviews and responsibilities:

- The Doctor: Rational and pragmatic, he is torn between his Hippocratic oath and his duty as a citizen. He sees the dictatorship as a repressive machine he could stop through passive inaction (by not reporting the tyrant’s aneurysm).

- The Priest: A defender of absolute moral principles, he refuses to condone the idea of sacrificing a life, even that of a monster. He advocates patience and divine justice, despite his helplessness in the face of the regime’s atrocities.

This ideological duel highlights the tension between individual morality and political pragmatism:

- Should immutable principles (not killing, honoring one’s oath) be upheld even at the cost of prolonged injustice?

- Or should these principles be transgressed in pursuit of a supposed greater good (ending a dictatorship)?

3. Political Assassination: An Act of Resistance or a Crime?

The play questions the justification of violence under a totalitarian regime. The doctor raises a fundamental question:

- Is allowing a tyrant to die an assassination or an act of legitimate defense on behalf of the people?

- Can murder be morally justified if it saves lives?

This dilemma aligns with a longstanding theatrical and philosophical tradition exploring tyranny and the legitimacy of regicide:

- It evokes Brutus and Caesar, Hamlet’s confrontation with usurpation, and modern debates on interventionism and the elimination of dictators.

- By referencing a young Hitler saved from drowning, the play deepens the reflection on determinism and individual responsibility in shaping collective destiny.

- The audience is directly challenged through fourth-wall-breaking addresses, asking: Would you have handed a rope to save Hitler? This mise en abyme actively engages the audience in the moral dilemma, turning theater into a space for political reflection.

4. Politics as a Moral Dead End

The play’s conclusion underscores the impotence of morality in the face of power’s complexities:

- The doctor succumbs to the temptation of a passive crime, yet without satisfaction or certainty about the consequences of his act.

- The priest does not denounce him, implicitly accepting that the world order might be altered by a transgression.

- The regime collapses, but revolution does not guarantee a better future: new violence remains possible.

Martinez thus warns against the cyclical nature of power, where the fall of a tyrant does not necessarily signify the end of despotism. He also highlights that resistance fighters, by adopting the oppressors’ methods, risk becoming the next dictators.

5. A Committed Play Without a Definitive Answer

Unlike militant theater that offers clear solutions, The Rope immerses its audience in moral ambiguity:

- It does not settle the debate between action and passivity, between revolt and acceptance.

- It rejects a binary vision of absolute good and evil.

- It poses universal questions about justice, responsibility, and power without providing simplistic answers.

The audience is thus invited to take a stance, reflecting on what it means to be a citizen in an oppressive society and on the limits of pacifism in the face of barbarism.

Conclusion

The Rope is a modern political tragedy where theater becomes a space for questioning morality and power. Through intense dialogue and direct audience engagement, Jean-Pierre Martinez explores individual responsibility under an authoritarian regime, the ethics of power, and the dangers of compromise.

By refusing to offer a clear resolution, the play confronts the audience with their own moral dilemmas, transforming theater into a site of engagement and reflection on the complexities of the political world.